from plant to paint to public

During a two-day event in front of industrial paint producer AkzoNobel’s art space, the history of allotments gardens and agricultural fields upon which the current Zuidas of Amsterdam is built resurfaced.

In September 2025 curator Jules van den Langenberg and artist Annee Grøtte Viken shared their research and plans for a new type of public artwork: A site-specific work that is based on a plant to paint to public principle.

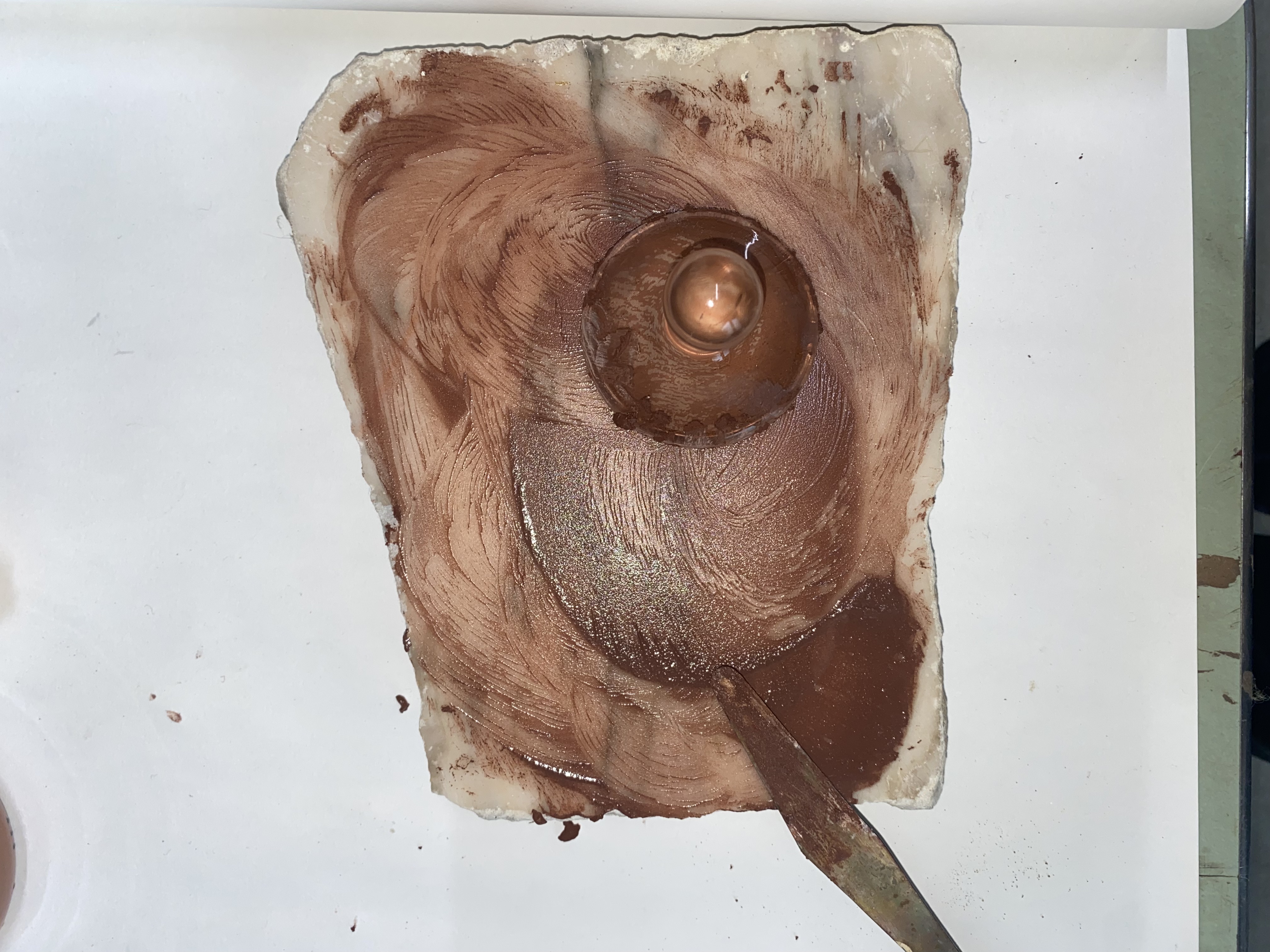

Curious neighbours, experts and nature lovers joined the transformation of an original 1960’s Friso Kramer Street lantern by ‘woodgraining‘, a traditional painting technique for imitating wood using natural pigments, water and linseed oil.

The goal? To bring back a sense of site-specific production to the streets and public spaces of the Dutch capital.

The project is part of a longer-term goal of the artist and curator in collaboration with the (Nelly&)Theo van Doesburg Foundation, to find a permanent destination for a series of circles used for cultivating flax in a neighborhood currently under construction. During sowing and harvesting, the circles become sites for social gatherings and seasonal harvest feasts. Once the flax is matured it is processed into linseed oil, traditionally used as a base for paint. Together with locally sourced pigments, an all-natural paint is then applied to benches, lanterns, and bins in public spaces, using age-old techniques of marble and wood imitation. This gives these everyday objects a monumental presence.

The plant to paint to public performance in the public space of Amsterdam’s Zuidas is an early prototype of this vision: a vintage street lantern, repainted with linseed oil paint and transformed into a vessel of stories, community, and craft.

To learn more about the plant to paint to public research in 2025 have a read in the article below by Laurens Otto.

ARTICLE

Progressive Conservation

Flax, one of the oldest cultivated plants, has served as animal fodder, and soil improvement through its deep roots, preparing fields for gardening. Its fibers served as linen canvas for painting, while its seeds yielded linseed oil, elemental in oil paint and varnish. However, it has now almost completely disappeared from industrial processes, especially paint making.

On 15 September 2025, participants with a direct interest in material culture[*] joined together at industrial paint and coating producer AkzoNobel’s headquarters in Amsterdam to discuss Annee Grøtte Viken’s proposal for a public artwork that integrates flax into the urban fabric. What follows is an amalgamation of that discussion.

Since 2021, Viken and curator Jules van den Langenberg have been collaborating with the (Nelly&)Theo van Doesburg Foundation to realize a public artwork that starts with a plot for flax to provide linseed oil and pigments as varnish and coating for various site-specific applications. In the long process of bringing this project to fruition, the Municipality of Amsterdam has now allotted a plot of land for the flax to grow for the duration of one year – as a proof of concept. The urgent question at hand thus is: how to create a scenario of flax fields integrated in neighborhoods, with the processes of sowing, caring, and harvesting, becoming a shared routine? How to entice new residents to live and work in an environment with the vibrant colors and patinas of linseed oil, that although slightly more unstable than chemical products, can provide a couleur locale?

In reviving flax, the goal should not be to sow in a demarcated aestheticized zone, but to fully integrate it in existing industrial or even pre-industrial practices. Bringing this process into public view would be a first step. Counter-intuitively, the few places where such a shift can happen are Amsterdam’s new high-rise Manhattanized neighborhoods, like Sluisbuurt and Zuidas. Right when new inhabitants move in, such a communal project could be adopted. The problem remains how to integrate such a sympathetic practice in the real economy. It’s possible to do small-scale experiments as an artistic practice, but it’s almost impossible to scale it up. The shift to natural materials would first need a cultural shift that redefines what counts as “good” and “sustainable”. There needs to be more space for deviations to allow for non-standardized processes and more unstable surfaces, linked to a general re-appraisal of craft and the knowledge embedded in these historic practices.

If conceptual recalibrations of craft, labor, industry, and production processes are hard to materialize in policy changes and direct action through an artistic project, this open-ended initiative has to rely on the totem of a finalized work. So far, and almost as a prop, the artist has transformed an original 1960’s Friso Kramer Street lantern through ‘woodgraining,’ a traditional painting technique for imitating wood using natural pigments, water, and linseed oil. And from there, by experiencing the sensorial qualities of that natural varnish – smell, touch – key stakeholders should be disposed to better see its urgency, to see examples of its application as a gentle push to start reverse-engineering the proposal and starting to implement flax again more broadly in our urban fabric.

The idea of maintenance, today so far removed from public view, could be the vector to implement this flax-work. Precisely the act of care and maintenance can in fact open up multiple new entry points; the act of caring for what’s already present could have more agency than to sail under the flag of an artistic project. In an ever more heated and unlivable planet, the question what can be maintained will be highly contested. To be able to conserve what is left will soon become a most viable form of progressive politics.

[*]Participants included: Hester Alberdingk Thijm (director, AkzoNobel Art Foundation), Wijnand Bruinsma (director, sustainability at AkzoNobel), Niek Hendrix (artist), Geertje Jacobs (director, European Ceramic Workcentre EKWC), Jippe Kreuning (miller at de Bonte Hen and advisor of the union De Hollandsche Molen), and Prof. Ann-Sophie Lehmann (Chair of Art History & Material Culture, Groningen University), moderated by Annee Grøtte Viken and Jules van den Langenberg.

THANKS

The two day presentation and research ‘Plant to Paint to Public’ was made possible thanks to the generous support of (Nelly&)Theo van Doesburg Foundation, Gemeente Amsterdam Zuid, Amsterdams Fonds voor de Kunst and Akzo Nobel Art Foundation. Thanks to all neighbors, experts and collaborators involved, especially Marjo van Baar, Sandberg Instituut, Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Hester Alberdingk Thijm, Augusto Pereira Silva, Boetie Zijlstra, Zaansche Molen, Geertje Jacobs, Paco Bunnik, Rosita Roosblad, Laurens Otto, Nieuw Zwanenburg, Sander van Wettum and Our Polite Society.